The next morning we were picked up by our tour bus to embark on a 10-hour tour around the main pre-hispanic archeological sites and other handcraft towns in between. We tried to find half day tours but they didn’t really exist. We weren’t sure how the all day tour would go with Ariela, but actually it was quite the success! Additionally, Ariela loved our hotel because we told her it was Coco’s house, but we weren’t so far off as the movie does take place in Oaxaca.

The first stop was Monte Alban. Only 9 miles from Oaxaca City, Monte Alban is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain in the central section of the Valley of Oaxaca

Our tour was mixed between some hippie Americans, some Chileans and other Mexicans. And while the tour was supposed to be in English, the tour guide’s English skill was a lot to be desired.

The partially excavated civic ceremonial center of the Monte Albán site is situated atop an artificially leveled ridge. It has an elevation of about 1,940 m (6,400 ft) above mean sea level and rises some 400 m (1,300 ft) from the valley floor, in an easily defensible location.

Ariela was enjoying the breaks with explanations, as she could eat her Oreos.

In addition to the monumental core, the site is characterized by several hundred artificial terraces, and a dozen clusters of mounded architecture covering the entire ridgeline and surrounding flanks.

Established by the Zapotec civilization around 500 BCE, it flourished for over a millennium before its decline around 800 CE. The site is a marvel of urban planning, engineering, and cultural achievement, offering insights into the sophistication of pre-Columbian societies.

The city was part of a broader Mesoamerican cultural network, engaging in trade and interaction with neighboring civilizations such as the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, and later the Mixtecs. It played a significant role in the development of writing, calendar systems, and artistic traditions in the region.

Ariela loved it because of the large grass area, she did not stop running for a couple hours!

Eitan had to capture her to take a photo!

More running. Probably prohibited as these were sacred grounds back then.

Monte Albán began to decline around 800 CE, possibly due to a combination of factors, including political instability, environmental challenges, and shifting trade routes. While the city was largely abandoned as a political and ceremonial center, it retained cultural significance for the Zapotecs and later the Mixtecs, who reused parts of the site for burials and rituals.

We told Ariela that she would get 1 superpower for each pyramid she climbed. She picked super-speed and princess-power, whatever that means.

On the way down, Ariela and Eitan recreated an official sacrifice.

The etymology of the site’s present-day name is unclear. Tentative suggestions regarding its origin range from a presumed corruption of a native Zapotec name to a colonial-era reference to a Spanish soldier by the name Montalbán or to the Alban Hills of Italy.

The view from the top was spectacular. The heart of Monte Albán is its expansive Central Plaza, a ceremonial and civic space surrounded by monumental architecture. Structures include pyramidal platforms, palaces, and temples, many of which were used for religious ceremonies, governance, and public gatherings. The plaza also served as a stage for processions and rituals that reinforced the city’s religious and political authority.

Anddd more running.

Sarah followed a few miles behind.

Monte Albán’s layout demonstrates the Zapotecs’ advanced understanding of astronomy. Many structures are aligned with celestial events, such as solstices and equinoxes. This alignment suggests that astronomical observations played a critical role in their agricultural calendar, religious ceremonies, and governance.

We started to make our way back, but not without Eitan climbing to every single pyramid for a photo. Sarah and Ariela decided to wait in the shade as the sun was getting too strong.

At its peak, Monte Albán had a population of around 25,000 people, making it one of the largest cities of its time in Mesoamerica. Its influence extended far beyond the Oaxaca Valley, as evidenced by artifacts and architectural styles found in distant region

In modern times, Monte Albán is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Mexico’s most important archaeological treasures.

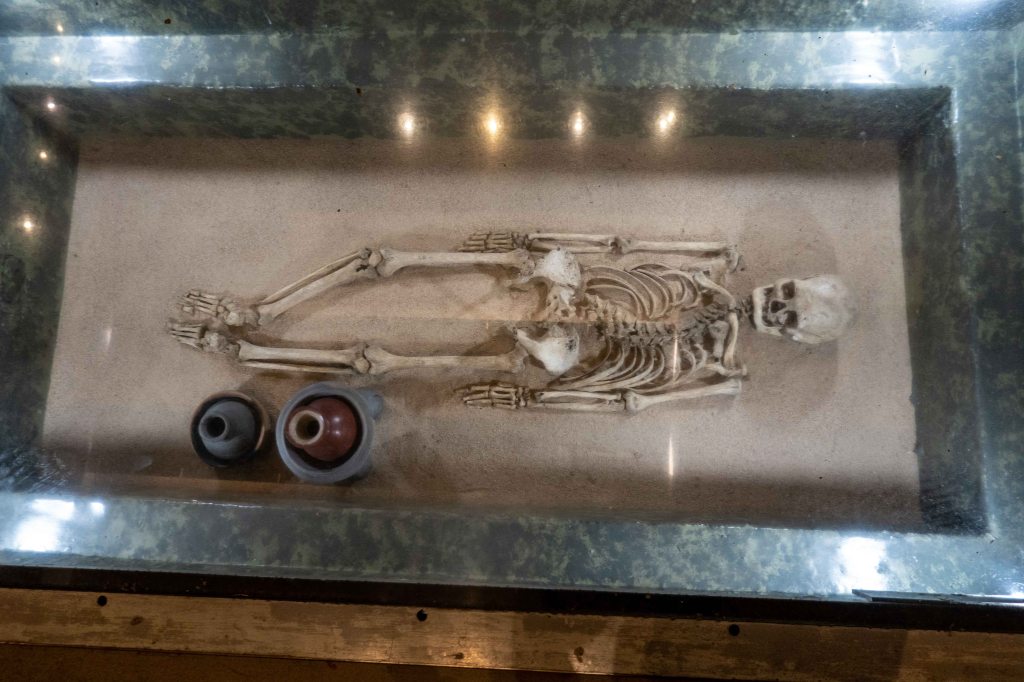

There was a little museum at the entrance/exit of the site. We showed Ariela the real skeleton, and she was unphased. Which actually seemed to be a logical reaction after seeing thousands of “fake” skeletons in the city due to Dia de Los Muertos.

They showed some nice archeological findings.

One of Monte Albán’s most enigmatic features is the collection of stone carvings known as the “Danzantes” (dancers). These bas-relief carvings depict human figures in contorted poses, often with exaggerated facial expressions. Initially thought to represent dancers, scholars now believe they may depict war captives, sacrificed individuals, or figures involved in ritualistic practices. The Danzantes highlight the Zapotecs’ artistic skill and their emphasis on ritual and warfare.

Back at the bus for another 40 min drive to our next destination, the Alebrije factory in the nearby town of Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán.

Alebrijes have transcended their folk art origins to become a global phenomenon. They are widely sold in markets, art galleries, and tourist shops across Mexico and beyond. The art form has also been featured in popular media, such as Disney’s Coco, where alebrijes are depicted as spiritual guides in the Land of the Dead.

Alebrijes are brightly colored, fantastical creatures that are an iconic symbol of Mexican folk art. These whimsical sculptures combine elements of real and mythical animals, often painted with intricate patterns and vibrant colors. They originated in the 20th century and have since become a significant part of Mexican cultural identity, blending traditional craftsmanship with artistic imagination.

The creation of alebrijes is credited to Pedro Linares López, a papier-mâché artist from Mexico City. In the 1930s, Linares fell gravely ill and, while unconscious, experienced vivid dreams filled with surreal landscapes and strange, hybrid creatures. These creatures had features of various animals—such as wings, horns, tails, and claws—and were shouting the word “alebrijes.” After recovering, Linares began recreating these dreamlike figures using papier-mâché, bringing the fantastical beings to life.

Linares’ work gained recognition when prominent artists like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo supported him, helping popularize alebrijes both in Mexico and internationally.

While Linares introduced the concept, the tradition of carving fantastical animals from wood emerged independently in the state of Oaxaca. Indigenous artisans from the region, particularly in the towns of San Martín Tilcajete and San Antonio Arrazola, began creating wooden alebrijes from the native copal tree.

Oaxacan alebrijes are typically hand-carved and painted with intricate, symbolic patterns. The designs often draw inspiration from Zapotec and Mixtec cultures, incorporating traditional motifs and spiritual themes. Unlike the papier-mâché versions, Oaxacan alebrijes have a more rustic and tactile charm due to their wooden construction.

Alebrijes are not just decorative; they hold deep cultural and spiritual significance. In some interpretations, they are considered spirit animals or guides, akin to the concept of “nahual” in Mesoamerican belief systems, where humans have a spiritual connection to a particular animal. The vibrant colors and imaginative designs reflect the Mexican worldview, where life, death, and the fantastical coexist harmoniously.

After Ariela chose her souvenir there, a beautiful butterfly Alebrije, we made our way to our bus for a quick drive to our lunch site.

We had an AMAZING buffet full of traditional Oaxacan dishes. We got stuffed with chile rellenos and mole tamales.

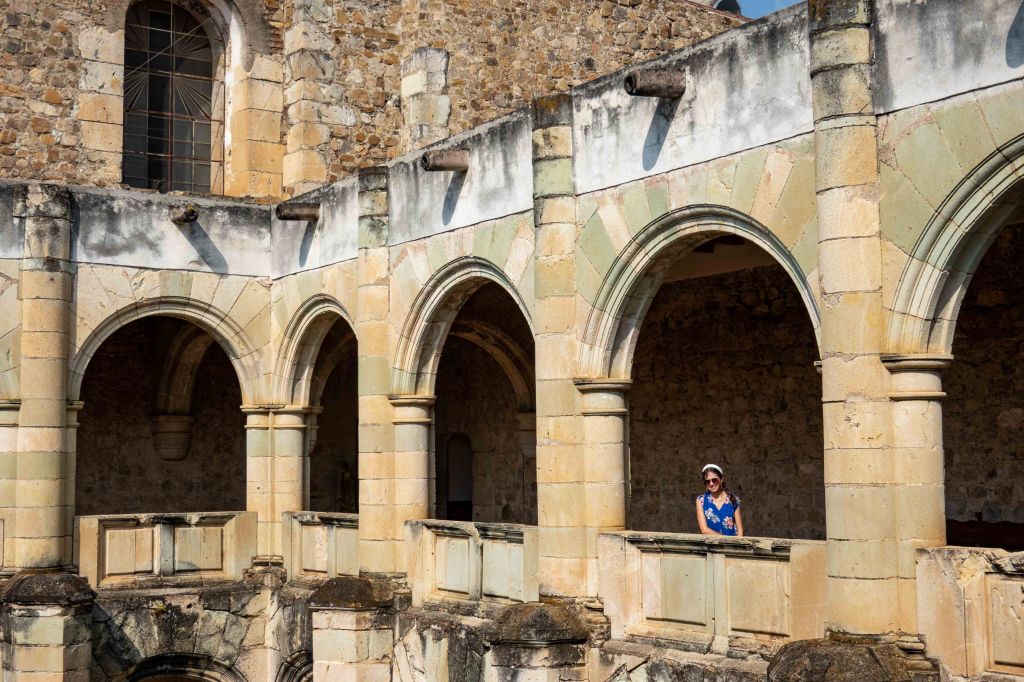

The next town was a quick stop at the Cuilapan Monastery. Also known as the Ex-Convento de Santiago Apóstol, is a remarkable 16th-century Dominican monastery.

It is one of the most iconic examples of colonial-era architecture in the region, blending indigenous and European artistic influences. Ariela really loved this princess castle!

Although the monastery was never fully completed, its grandeur and historical significance make it a prominent site for understanding the cultural and religious transformation of the area during the early colonial period.

The monastery was built between 1555 and 1570 by the Dominican order, which was instrumental in evangelizing the indigenous populations of Oaxaca. The Dominicans chose Cuilapan as a site due to its proximity to indigenous communities and its strategic location in the Oaxaca Valley. The complex was dedicated to Santiago Apóstol (Saint James the Apostle), a symbol of the Spanish conquest.

The open chapel is one of the most iconic elements of the monastery, designed to accommodate large gatherings of indigenous converts who were accustomed to outdoor ceremonies.

The decorative elements of the monastery incorporate indigenous symbols, such as floral and geometric patterns, demonstrating the syncretism between Spanish Catholicism and native traditions.

The Dominicans taught Spanish, Christian theology, and European agricultural techniques to the local population.

The site is closely associated with Vicente Guerrero, a leader in Mexico’s War of Independence. Guerrero was executed in Cuilapan in 1831, and a memorial plaque marks this event.

By the late 16th century, the monastery began to decline due to the diminishing number of friars and financial difficulties. It was eventually abandoned but has remained a significant historical site and normal church services.

We visited inside the monastery but there was really not much to see.

An empty roof yeey!! Good view though.

The cloister, where the Dominican friars lived and worked, is a two-story structure with a courtyard surrounded by arched corridors. It includes cells, a refectory, and a chapter house

The next stop was a workshop of black pottery!

Black pottery, or “barro negro”, is one of the most iconic and traditional crafts of Oaxaca, Mexico. Renowned for its glossy, jet-black finish and intricate designs, this pottery style originates from the town of San Bartolo Coyotepec, located just outside Oaxaca City. The craft has deep roots in Zapotec culture and has evolved over centuries, blending ancient techniques with modern innovations.

We got a live demonstration where the man created a pot from scratch in about 3 minutes. Pretty impressive.

This clay is known for its plasticity and high iron content, which contributes to the black color during firing. To achieve the glossy finish, the surface of the pottery is polished with a smooth stone or piece of quartz before it is completely dry. This step compresses the clay particles, creating a reflective surface.

There was a funeral ceremony happening right outside. Music bands and fireworks are integral elements of these funerals, reflecting the Oaxacan belief in honoring the deceased with a vibrant farewell that celebrates their life and aids their journey to the afterlife.

We bought a small pot and jumped back in the bus to take us back to our hotel for a nice dinner where Ariela threw a tantrum of epic proportions for unknown reason.

Anyways, we calmed her down and she was excited for our back to the hotel with a popsicle.

We did end up having to switch hotels for this night only as our normal hotel did not have availability for the full 5 nights. Its was a really nice room, as well walking distance from the other one, so Eitan just moved the bags back and forth.

Bonus Pic of Day:

The copal tree is a culturally and spiritually significant tree in Oaxaca, Mexico, and across Mesoamerica. Known for its resin, which is used as incense in rituals, and its wood, which is crafted into traditional alebrijes (Oaxacan folk art sculptures), the copal tree has deep roots in the region’s indigenous traditions and daily life.

The resin of the copal tree is burned as incense in religious and spiritual rituals. It is considered sacred and is believed to purify spaces, cleanse negative energy, and create a connection between the physical and spiritual worlds.

In Oaxaca, copal incense is prominently used during Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrations, where it is burned on altars to guide the souls of the departed back to the living world.